Louis L'Amour complained about this in the '70s. He knew his stuff because he was exacting in his historical research. Sorry Toshiro Mifune, but the Seven Samurai isn't a perfect translation into the Magnificent Seven. Americans do not do unarmed peasants.

Black Bart couldn't terrorize a town full of Civil War veterans who were trained in warfare. Maybe he was the fastest gun in the west but he could still die from a shotgun blast in his back. Or if the town is mad enough, he might face six shotguns with the warning that you might kill one of us but you won't kill all of us and you'll be just as dead.

L'Amour claimed the face off at the edge of town was exceedingly rare. And when it did take place, a big guy full of adrenaline won't go down with only one shot. Because he had been a boxer as a young man, his fistfights are often better than his gunfights.

A gunfight isn't a duel between magical weapons where one shoots and the other dies. It's a fight where damage causing attacks are exchanged until one or both sides can no longer hit the other.

People who know something about guns understand this. Most of what you read in books or see in movies does not reflect this understanding. The gunfight brings the climax of the story with a bang and you immediately segue into the denouement and start selling the sequel.

Mindful of this I was reading a thumbsucker about the N most important Science Fiction novels. I was impressed by the inclusion of stories that inspired nothing but eye-rolls when I tried to read them, and I was impressed by the omissions.

Mindful of this I was reading a thumbsucker about the N most important Science Fiction novels. I was impressed by the inclusion of stories that inspired nothing but eye-rolls when I tried to read them, and I was impressed by the omissions.(Likewise, I was reading a collection of the best SF stories of last year and after reading one that I knew was excellent, I was impressed by the next two that made me think, "what made that special?" I suppose I would have to be a Social Justice Warrior to understand.)

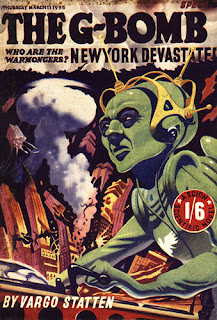

I figure an SF novel is not important if it reiterates The Message that the SJWs are pushing, but it is important if it changes the direction of the genre. Someone in the '40s and '50s got everyone to writing novels with a rocket ship on the cover. Someone in the '60s got everyone to writing novels with a mushroom cloud with grateful dead in the foreground on the cover. I'll call those important SF stories.

Tom Clancy's Hunt For Red October was important because it got a lot of stories about the Reagan military build-up. The whole field of military SF took off at this time.

But let's backtrack to those 1950s B-quality SF movies. Not the high brow ones like Forbidden Planet, but the cheap ones with giant ants, spiders, etc. You know, like Attack of the 50 Foot Woman. The ones made on the other side of the pond were a little more posh, like The Day of the Triffids, but they all followed the same pattern:

Radiation or something mutates ants into the size

of houses. Or a space comet drops spores on Earth and blinds people while the spores grow into giant people-eating plants. In such a movie the first reel is spent learning Something is Not Right. The second reel is spent convincing someone official to Take Action. The third reel is then divided in two halves: Our Guns Have No Effect on the monster, and finally Something Trivial devastates the monster.

(Something Trivial? Consider something as ubiquitous as water. If you're the alien in Signs, it'll kill you. Same for those carnivorous plants in Day of the Triffids. (Don't forget the wicked witch of the west.) In these movies it serves as Something Trivial to be pulled out at the Dark Moment to act as a deux ex machina and save the day.)

This happens because if guns are magic, then the writer can turn off their magic.

All this made me grow bored and tired of the entire Horror genre. I wanted to just yell at the idiot who tries to escape the chainsaw wielding fiend by jogging backwards in the forest. The slasher movies were the most annoying. There were tantalizing glimpses of a better way. The scene in Nighthawks with Sly Stallone in drag, or the world's shortest slasher film.

But the old tired pattern is risible to anyone familiar with guns. If you shoot a vampire, the kinetic energy of the round has to go somewhere as it goes through the monster's body. And if the round doesn't interact with the matter of the vampire, then how can the monster interact with other matter, say the girl's neck to be bitten or her blood to be sucked?

This sets the stage for someone like Larry Correia to write Monster Hunter International novels. He's a firearms instructor and he's trained civilians and lawmen in how to use guns effectively. You can call him a gun nut, but you'd better smile when you say that.

He respects guns enough to have the round do SOMETHING to the monster, even if it is less than sufficient to kill the beastie. Consider the opening scene of the first Monster Hunter International novel. Our Hero encounters a werewolf. You know, werewolves cannot be killed except with wolfbane and silver bullets. But Our Hero empties his gun in the beastie and it keeps coming, and he uses his fists. It keeps coming, he pushes it out a fourth-floor window, then he drops a desk on top if it.

No wolfbane, and no silver bullets. The werewolf (a young one) cannot regenerate fast enough to survive the blunt force trauma of a desk falling on his head.

At some point, even monsters have to obey the laws of physics. And that awareness is what Larry Correia brought to the telling of monster stories. It changes the entire horror genre. Instead of being helpless, or utterly dependent upon a stupid gimmick, the forces of good can innovate and come up with better ways to fight evil. When "our guns have no effect on the monster" let's try bigger guns. (And if your heroes don't have bigger guns, they can make do like the Finnish did when they beat the Russians in WW2. Like this.)

Making guns less magical

is a very helpful thing for the horror genre. And I think that when more writers realize that guns are not magic, they'll use them more effectively in their storytelling. This makes Monster Hunters important SF/horror stories.